Like most writers, I've woken up many times in the grip of a dream that seems like perfect material for a novel or a poem. Maybe you get as far as jotting it down before going back to sleep. When you wake up again, there's nothing there that makes sense. Dreams are fascinating to live through, but nonsense in daylight. Or, worse, they make too much sense - it's embarrassingly obvious what waking thoughts and experiences got translated into them. Either way they don't generally make good literature. And yet the urge to use them remains. Dreams are narratives, after all, and their very strangeness gives them the element of surprise we value in fiction. For writers who are fascinated by their own art (and what writer isn't?) they make a great metaphor for writing itself. They are used as a conventional framing device in,for example, Piers Plowman, The Divine Comedy, Alice. When we read them in this form, we're well aware of the conventions; the dream is not a real dream, and only retains those dreamlike characteristics that fit the writer's purpose.

Like most writers, I've woken up many times in the grip of a dream that seems like perfect material for a novel or a poem. Maybe you get as far as jotting it down before going back to sleep. When you wake up again, there's nothing there that makes sense. Dreams are fascinating to live through, but nonsense in daylight. Or, worse, they make too much sense - it's embarrassingly obvious what waking thoughts and experiences got translated into them. Either way they don't generally make good literature. And yet the urge to use them remains. Dreams are narratives, after all, and their very strangeness gives them the element of surprise we value in fiction. For writers who are fascinated by their own art (and what writer isn't?) they make a great metaphor for writing itself. They are used as a conventional framing device in,for example, Piers Plowman, The Divine Comedy, Alice. When we read them in this form, we're well aware of the conventions; the dream is not a real dream, and only retains those dreamlike characteristics that fit the writer's purpose. In The Arabian Nightmare, Robert Irwin concentrates on two characteristics of dreams, the difficulty the sleeper sometimes has in telling sleep from waking, and the nesting of dreams within dreams. There is also a dreamlike strangeness due to the magical element that appears from time to time - but because of the blurring of sleep and waking, we never know if it's real or dream magic. Irwin's dreams are conventional - we are well aware that they are just another mode of storytelling. But there is one novel I know where the dreams are both an effective part of the narrative, and genuinely dreamlike.

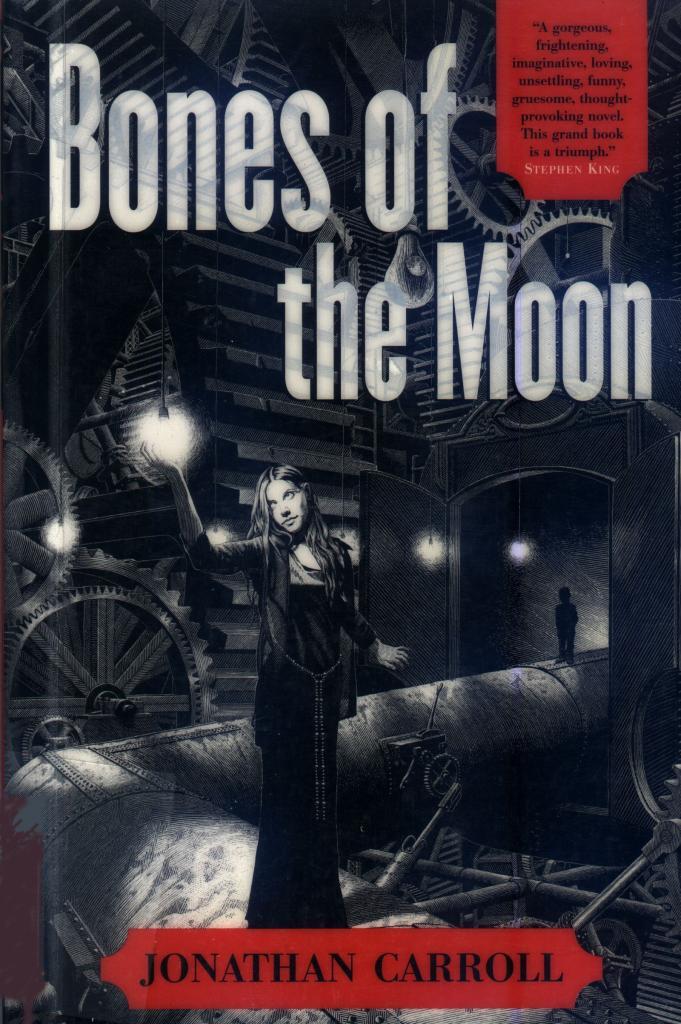

Cullen James is a happily married woman living in New York with her husband and baby daughter. But there are a few shadows in her life. In the apartment downstairs, as we learn in the opening sentence of Bones of the Moon, a boy has gone crazy and killed his mother and sister with an axe. Before her marriage, Cullen herself had a series of unhappy relationships, culminating in an abortion about which she still has feelings of guilt. A charismatic but frightening film director is making insistent passes at her. And Cullen is suffering from her own version of the Arabian Nightmare, a series of intensely vivid dreams which connect together to form a continuous narrative:

How strange it was to eat glass and light. All of the food on the table was laid out beautifully and precisely. The spread would have looked delicious if everything wasn't transparent; splashing the light from the icy chandelier hung high and huge over the crystalline dining-table.The dreams take the form of a quest through a magical land called Rondua. Cullen's companions are a number of talking animals, notably a hat-wearing dog called Mr Tracy, and a small boy, Pepsi, who is her son in the dreamworld (and, as we soon realize, a projection of her guilt about the abortion). They are searching for five magic tokens called the Bones of the Moon. And for all their surreal quality the dreams have a consistent structure: as they travel through the different regions of Rondua and collect the bones, the dream story moves towards its climax, a confrontation with the villainous Jack Chili. Meanwhile, Cullen's waking life is becoming more disturbed. The 'axe-boy', now in prison, has begun a worryingly obsessive correspondence with her. She seems to be developing supernatural powers; and the film director, Weber Gregston, starts having the same dreams.

Pepsi picked up his clear hot-dog wrapped in its clear bun and took a big bite. His walking stick leaned against the chair and was the only patch of colour around. Exposed to the sun for days on our walk here, the sticks had burned or ripened... changed from their original grey-brown to a deep, vivid purple.

Sizzling Thumb had mine over his lap and kept petting it like a cat. 'Your tapes arrived without chicken.'

Bones of the Moon is a brilliantly constructed fantasy thriller, though it teeters on the edge of sentimentality at times. But what really sets it apart is the portrayal of the dreams. Stephen King, an admirer of the book, has written: 'When has any novelist last caught so perfectly the weird but matter-of-fact experience of dreaming?' Never,as far as I know. These are the most dreamlike dreams I have ever seen in fiction, as absurd as they are compelling.

It's a nice piece of synchronicity that the author shares his surname with the author of the Alice books (though Lewis Carroll,of course,is a pen-name, while Jonathan is a Carroll by birth). He has written some fifteen novels, and all of those I've read show the same dazzling originality and imagination that characterize Bones of the Moon. Neil Gaiman, as well as King, is a fan. Carroll's first two novels, by the way, are published in the Fantasy Masterworks series, which I've mentioned before: I intend to blog about one of them at a later date.

Next time I'll be writing about an early, lesser-known novel by a major British post-war novelist.

No comments:

Post a Comment